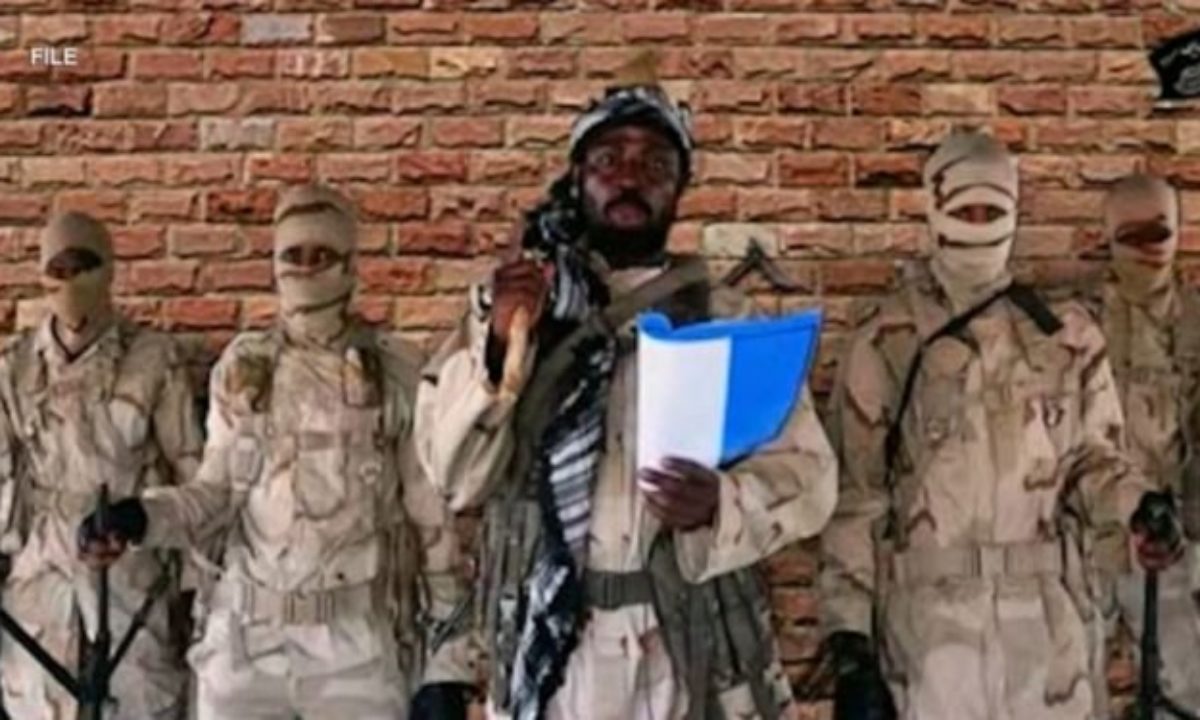

Founded in 2002, Boko Haram was culled from the words “book haram” and interpreted to mean “Western education is a sin or forbidden.” Its founder, Mohammed Yusuf, sought the “purification” of Islam in the northern region of Nigeria comprising 19 states. The region is further divided into the North-East, North-West and North Central.

Boko Haram has from inception taken a grip of the North-East, which has six states, namely Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe. Of those six states, the terrorists have mainly occupied Borno, Adamawa and Yobe – with Borno being the centre of their operation.

It’s apparent from MFWA’s interactions with reporters and residents that, the sect’s activities were initially non-violent, but as Yusuf gathered more disciples and preached against Western education, the sect became more radicalised, leading to attacks on schools, churches and mosques thought to be too liberal in their Islamic teachings. The group wanted strict adherence to Sharia law and sought an Islamic state in the North. Yusuf, who preached at a mosque in Maiduguri, wanted no books to be read other than the Quran.

When he was killed, a new leader arose named Abubakar Shekau, who turned the Islamic sect into a full-blown jihadist group. The members’ beliefs are centred on strict adherence to Wahabism, which is an extremely strict form of Sunni Islam that sees many other forms of Islam as idolatrous. The group denounced the members of the Sufi and the Shiite sects as infidels. They frowned on what they described as the Westernisation of Nigeria.

Among other notorious attacks carried out by the sect was on April 14, 2014, when it kidnapped 276 teenage girls from a secondary school in Chibok, Borno State.

After learning of the kidnap, the Twitter hashtag #BringBackOurGirls became one of the most trended hashtags worldwide and inspired several other campaigns on various social media websites in hopes of pressuring the Nigerian government to do more to recover the girls.

Tearful Testimonies of Traumatised Reporters

But behind the gory headlines are a crew of troubled but heroic journalists who have been in the frontline, braving and biting bullets to bring the news to the public. Timothy Olanrewaju, a reporter for The SUN Newspapers in Nigeria, is one such journalists. He has been covering the Boko Haram insurgency from Borno State since 2003. This was a year after the sect was founded by Mohammed Yusuf.

Of the 24 years Olanrewaju says he has been practising journalism, 19 has been spent reporting from Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State and the centre of the Boko Haram insurgency.

“One of the first challenging issues I faced reporting from the theatre of Boko Haram is lack of training. Most of us were not trained on how to report terrorism. And as such, we were seriously endangered. Some of us have sustained injuries in the field. As a matter of fact, I was once an internally displaced person,” he told MFWA.

But after a while, through reading tips by war journalists and undergoing training organised by some agencies, Olanrewaju said he learnt about reporting from a conflict zone.

“It was at one of the training that I learnt that as a journalist living in a conflict zone, you don’t stay in one place. So, I had to rent three houses at different locations in the city. But even when I had different houses, terrorists would write to me and fellow journalists that they knew our houses. I had to relocate my family out of here in 2011 because of the numerous threats.”

At another training held in Kenya on reporting from conflict and sensitive environments, Olanrewaju said he learnt that he needed protective gear comprising a bulletproof jacket, helmet, first aid box, transit kits, and others.

“Unfortunately, my employer did not get these items for me. All they wanted was for you to write stories. From my findings, most Nigerian media companies do not provide capacity building for their journalists.”

In 2017, the journalist said he was gifted a bag of protective gear by CNN’s Richard Quest, who he had met at a training workshop.

Olanrewaju also complained about poor welfare for journalists reporting from the conflict zone, saying his salary of less than N100,000 ($263) per month had even been halved due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In spite of that, he has had to buy a camera from his savings to do his work.

He said, “Nobody also cares about providing hazard allowance for journalists like me reporting from a conflict zone. Salaries are not paid timely let alone hazard allowance. The salary I was being paid seven years ago is what I am still earning – which is the same salary that a reporter in normal zones is earning.

But on top of the numerous issues faced by journalists in the conflict zone is trauma. After covering terrorism for about 17 years in Borno State, Olanrewaju suggested during his interview with MFWA that he was also suffering trauma.

He said, “Some of us are facing mental health challenge. From my interaction with my colleagues, every journalist who has covered Boko Haram insurgency in Borno State for more than 10 years has mental health challenge. I can say this for a fact.

“Many of us saw people being slaughtered, we saw blood, we saw corpses on the streets. Unfortunately, most media companies don’t have departments for psychosocial support, so we are practically on our own. In fact, nobody has ever asked me how I am coping here.”

Njadvara Musa, a journalist for The Guardian Newspapers also based in Maiduguri, said he has faced trauma while reporting from the conflict area. The 64-year-old said he has constantly faced threats to his life and is traumatized. He cited repeated incidents of fatal attacks on the convoy of the Borno State Governor, Prof Babagana Zulum which was accompanied by a group of reporters including himself.

In 2020 alone, within a year of becoming governor of the state, the governor’s convoy has been thrice attacked by Boko Haram terrorists – first on July 29 in which the insurgents reportedly killed five people, including three policemen; second on September 25 when the governor travelled to Baga to prepare for the planned return of internally displaced persons. [Baga is a town once controlled by the insurgents.]

During the attack, 15 persons – eight policemen, three soldiers and four civilian joint task force operatives – in the governor’s convoy were reportedly killed.

Barely two days after the second attack, Zulum’s convoy was again attacked by terrorists on September 27. No death was recorded, but some of the vehicles in the convoy were reportedly destroyed, including a bus conveying journalists. Musa, who is from Gwoza Local Government Area of Borno State, said such attacks have left many journalists afraid of their lives.

“I started reporting on Boko Haram since July 29, 2009, so it’s been 11 years of covering the insurgency. Many journalists have had to flee from here when they couldn’t cope again. Only a few journalists are left here. If there was more support, especially financially and psychologically, they probably would have stayed,” he told MFWA.

Recounting his experience when the governor’s convoy was attacked by Boko Haram on September 25, he said, “I had to lie on the ground to escape gunfire between the governor’s security agents and the terrorists. It was a heated exchange of gunfire. Eventually, around 15 security agents were killed.”

Musa also complained about lack of protective gear to use while doing his job. He said “Many journalists here like me don’t have the protective gear, so it limits how we cover the crisis. We usually rely on our native intelligence to escape from attacks. “The military has supported us on several occasions by giving us helmets and bulletproof vests when we are going to cover their operation. But of course, we return their protective kits when we return from such special assignments.”

Ahmed Mari, a journalist for The Champion Newspapers, has been reporting on the Boko Haram crisis since 2009, also shared his experiences with MFWA. He has also received numerous threats from the terrorists, although the security situation is now gradually improving.

He said “In the past, the terrorists would send text messages to journalists that they knew us very well. Sometimes they would ask why we were not reporting them well. They organised teleconferences for us and there they would threaten to kill us if we didn’t do their bidding.

“They considered us as their enemies and drew a battle line with us. Some of my colleagues have had to flee here because of continuous threats. I remember there was a particular time we had to help a colleague escape to Abuja because the insurgents were after his life.”

Mari also asked media owners to support journalists covering conflict, especially in the area of psychotherapy.

“There is a way that what we have seen has affected our mental health. I have somehow accepted my fate that one day, I would die, because anything can happen. I’ve seen lots of corpses and blood. It’s a lot I have taken in,” he said.

Apart from Borno State, the epicentre of Boko Haram, two other states in Nigeria, Yobe and Adamawa, are mainly occupied by the terrorists.

Joel Duku, a reporter for The Nation Newspapers in Yobe State, said he and other journalists in the state sometimes got scared because of the occasional shootings by terrorists.

He said, “Life here has been very difficult. Some of us were not exposed to conflict reporting prior to the Boko Haram insurgency; we learnt on the job. We still get scared sometimes.

“For safety reasons, there are still many places we can’t go to report. Things are gradually restoring to normalcy but the trauma the insurgents has left with many of us journalists still remains. Even till now, we have to be careful of what we say, and when and where we say it”, the journalist sobbed.

“When we hear gunshots or sounds of a bomb explosion, we are afraid of our lives and those of our families. We can’t sleep with our two eyes closed. Unfortunately, in terms of welfare and psychosocial support for journalists, it’s not really there,” Duku bemoaned.

Similarly, a journalist with one of the government-owned television stations in Yola, Adamawa State, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said she had been exposed to trauma due to years of continuous reportage on Boko Haram insurgency.

“It’s been close to a decade of covering Boko Haram insurgency in the North-East, and seriously speaking, I’m mentally frustrated. There are times I wouldn’t feel like eating food when I recollect how innocent souls, especially children and women like me, have been murdered by the insurgents. It takes a toll on my health,” she told MFWA.

Psychotherapy tips for traumatic journalists

An expert in psychotherapy at the Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ogun State, Nigeria, Oladotun Adeyemo, noted that journalists reporting from conflict zones might be experiencing trauma due to either of two factors – personally experiencing attacks, or witnessing attacks on others.

“What they are passing through could be acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depending on the duration of the trauma. ASD and PTSD are due to having flashbacks of what they have experienced, that is, re-experiencing what they have experienced. ASD lasts for a short time, maybe a week or two, but PTSD lasts longer. The reason for the flashbacks is because the brain does not sleep, even when someone is sleeping,” Adeyemo explained to MFWA.

For such journalists to overcome trauma, the psychotherapist said they needed to weaken the structures of the brain that were bringing the flashbacks. He said, “They need to let the brain flush out those flashbacks by going to a therapeutic environment. They may not stop having those flashbacks immediately, but over time, if they are subjected to a therapeutic environment, the flashbacks will go away.

“This they can do by consulting clinical psychologists to help them relieve their experiences in a manner that will not agitate them again. Professionals know professional ways to flood the brain of someone with trauma with ‘positive or happy stories.’”

But should journalists have difficulty consulting psychotherapists, Adeyemo advised them to seek support from people closest to them, and also engage in physical activities like walking and dancing as such activities have the capacity to lighten up the mood.

He said, “Alternatively, they can ask for ‘significant support’ – that is, from people closer to them like their spouses and colleagues. They should find shoulders to lean on.”

However, consulting professionals remains the best tip for journalists going through trauma, Adeyemo emphasised.

Safety protocols for journalists in crisis areas

A security researcher at the Nasarawa State University, Keffi, Nigeria, Prof Olayemi Akinwumi, urged journalists covering conflict zones to always look for best practices in terms of their safety.

“When reporting from a conflict zone, they should be armed with safety gadgets. They are also encouraged to go for more training on conflict reporting.

“The Nigerian Union of Journalists can partner organisations that can specially train journalists on how to protect themselves in a conflict zone. Media organisations should also ensure to provide comprehensive insurance plans, including life insurance, for their reporters in conflict zones,” Akinwumi told MFWA.

Also, besides improving the working conditions of reporters in conflict zones, a security expert-cum-media analyst based in Lagos, Nigeria, Judith Okon, offered some safety tips for the journalists.

First, she asked the journalists to make life protection their top priority by wearing protective equipment such as helmet, life jacket, and gas mask.

“The journalists should also follow regular and systematic professional training about news coverage in a hostile environment and share their daily locations and schedules with the NUJ branch or at least one colleague in their places of assignment.

“They should also keep the distance from conflict zones before making live coverage for TV and web and remain cautious when unknown individuals offer them news opportunities because of kidnapping attempts.

“Also, they should ensure that their identification cards are clearly visible for the authorities or any groups. They should never stay alone after traumatic experiences by sharing their stories and feelings with at least one person.

“Lastly, I would say they should take a break and ask for relocation, even for a short period, after the coverage of traumatic experiences. When the post-trauma effects are lasting for a long time, they should seek professional help,” Okon told MFWA.

Nigerian journalists’ union advocates better welfare for members

Speaking with MFWA, the President of the Nigerian Union of Journalists, Chris Isiguzo, said the union had from time to time reached out to media companies to provide better welfare and offer psychotherapy for journalists covering conflict zones.

“For journalists operating in conflict areas, we have been reaching out to media owners that before sending reporters to such areas, they are supposed to properly train and provide proper remuneration for them. Also, comprehensive insurance packages should be provided for such journalists,” he said.

“So on our part, we have always advocated that journalists, particularly those reporting from conflict areas, should be well remunerated. Unfortunately, we have the problems of poor and irregular remunerations in the media industry. They are commonplace and they are huge challenges that journalists are facing. Journalists are not safe in the North-East. And now, conflicts are escalating in other northern states like Katsina, Sokoto and Kaduna,” Isiguzo added.

“As I speak, I have yet to learn of any media house that has a full insurance package for its journalists. The necessary legislation is not there. We have written letters to the Presidency and the National Assembly on this. And once the necessary legislation is not there, the challenges will linger. But we will not relent until we get to the place of our dreams,” Isiguzo observed, adding that “this is why we are also pushing for a Media Enhancement Bill that criminalises any action that does not empower and protect journalists at workplaces.”

The MFWA celebrates these gallant journalists whose sacrifices have enabled the Nigerian and international audience follow the Boko Haram insurgency and appreciate its full impact on the lives of the people of Northern Nigeria in particular. We urge media owners and managers, civil society and the government of Nigeria to provide the necessary capacity and logistics support to the journalists on the frontline of the Boko Haram conflict.